The Genesis

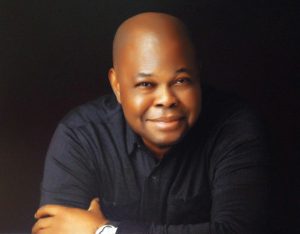

Dr Okey Anueyiagu proved to be of dramatic and phlegmatic disposition all at once. He came across as a controlled explosion, with a calm externality that belied a fiery intentionality.

Awka Times editors had tracked this urbane jet-setter across the globe seeking an interview on the extraordinary new project which his eponymous foundation is running: the funding, building and equipping of brand-new buildings donated to primary schools dotted around Awka, along with the training of teachers and curriculum modernization.

He had agreed to do an interview, pending his landing back in Nigeria. But as we awaited word of his return, Awka Times’ meticulous search for the Person of the Year ended with the selection of Dr Anueyiagu as the laureate! Our original interview plan thus took on an added significance.

Dr Anueyiagu finally returned to Nigeria, and we mobilized to move men and machine to meet with him in Lagos. At first, he would have none of the ceremony – preferring, it seemed, that the project bear its own silent testimony. But persistence overcame resistance and we finally got the good doctor to open up.

We present below our interview with Dr Okey Anueyiagu: accomplished author, philanthropist, educator, entrepreneur, art collector and Awka Times Person of the Year 2019. We ranged across his formative influences and his philanthropy, as well as political and development issues in Awka. He was unsparing, even daring, about the glaring conditions in his beloved hometown.

The interview is edited for length but with a sensitive touch that preserves the penmaster’s pulses.

(The excerpt below picks up after opening biographical questions – See Profile).

On His Antecedents

Awka Times Magazine (ATM): What are your earliest childhood memories – specifically about Awka and also where you grew up?

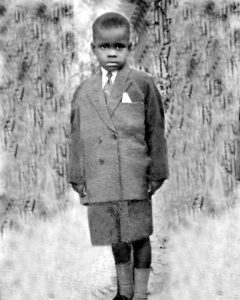

Dr Okey Anueyiagu (DOA): I was born and raised in Kano City, in Northern Nigeria. The city was a bustling cosmopolitan centre of mainly Hausa-Fulani indigenes who were mostly nomadic in nature and traded in goods and services. There were also a large composition of other tribal settlers of mainly Igbo and Yoruba extraction that made up the teaming population of the city.

My parents – who lived and worked in Kano – periodically took me and my siblings to Awka where we spent memorable times in the then beautiful town with our maternal grandparents. The memories that Awka left me with were endearing and can only be described in one word: enchanting. The level of joy that I experienced each time the trip to Awka was upon us can only be imagined.

Awka was a peaceful town steeped in deeply exhilarating Igbo culture and tradition. The Egwu Imoka festival was what I looked forward to the most. I loved the very colourful masquerades and the rituals, and the tradition of the masquerades living up (oso n’ogba) to make the trip to Umuokpu village and back to the Imoka shrine. To me then, nothing was more enchanting than to partake in these festivities. I loved the food, the banters and happiness and the spirit of brotherly and sisterly love that were the hallmarks of the Imoka ceremonies. To miss attending these festivals then was unfathomable, and my father made sure I did not. For this, I owe him a world of gratitude, for I believe that it formed part of my love for our town Awka and my admiration of its values, language and culture.

Another everlasting and enduring memories of my early contact with Awka was when, in the early 1960s, my grand uncle Nwaokafor Ndum – father of Barrister Amanke Okafor – took the Ozo title. We had returned from Kano to attend the ceremony. It was the most elaborate traditional event that I had ever witnessed. It lasted for 21 days with the slaughtering of countless numbers of cattle (as it seemed to me). Various dance troops and masquerades attended. Each day presented different functions, colours, dances and delicacies. The abacha ncha, avbulu, aghalighali, aka aga, umeju anu, ugbogili na anyu nda, and all other items of specialized Awka delicacies were served. These days, I hear that anyone can take this exalted Ozo title, and that the prestige it carried in the past has evaporated.

ATM: What are the most memorable lessons you learned growing up?

DOA: Most of the lessons I learned growing up were the ones I got from my parents who, I believe, lived exemplary lives. Some of these lessons were passed down in unconscious ways. I believe now that through the process of socialization and cognitive learning I picked up various good examples of how to become a useful citizen of the world. Through my father, I acquired the attitude to be humble no matter how successful one may become. He taught me to be fearless and upright, and to never be spiteful even of people who do not like me. He always told me to treat everyone better than you would expect them to treat you, and to be kind to the poor, the sick, the deprived and the needy.

The lessons I got from my mother was that of loving God and loving people. She made us pray several times a day and by so doing imbibed in us the fear and spirit of God. For this reason, it has become very difficult for me to take any action without contemplating what the consequences would be before God. The lack of religion in our homes and schools today, I think, is the direct and consequential reason for the high rate of crime in our societies.

Over the years, I have continued to strive to imitate, emulate and follow in the footsteps of my parents, their paths of honour and integrity, to be a beacon of their shinning and unblemished lives. I always consider myself blessed and lucky to have had my parents’ incomparable legacies because these shaped my past and my present, and will fuel my future aspirations to match their noble ideals.

ATM: Your father was a great man in his own right. What did you learn from him that informs your philanthropic disposition?

DOA: I learnt from my father to give quietly. He contributed a lot to his society but he made sure that what his right hand did his left hand did not know. From my childhood I recognized my father’s philanthropy. He was the founder and the main mover and contributor to the establishment of the Ibo Union Schools in Northern Nigeria. He was the Chairman of the Ibo Union Scholarship Trust that sponsored the education of many Igbo sons and daughters locally and overseas. The Igwebuike Grammar School and the Amaenyi Girls Secondary School in Awka were his ideas and he pioneered their establishment. His philanthropy was monumental, but he never talked about them. It will be very difficult to follow in his footsteps.

ATM: Do you think that your father’s progressive politics informed your philanthropic orientation?

DOA: My father was an astounding journalist, a conscientious businessman and a consummate politician. He was indeed a great man who had his odyssey through journalism, politics, business and community service whilst sticking to the path of honour, honesty, integrity and hard work. I diligently watched him go through these processes.

He became deeply involved in local, regional and national politics. He played considerable role in the politics of pre-independence and his activism earned him occasional detention by the British colonialists. He was an active member of the leading political party then, the NCNC, which was formed by his mentor, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe and others. He rose to become chairman of the party in Northern Nigeria, having started out as a Councillor in Waje. In the lead-up to the December 1964 elections, NCNC established the United Progressive Grand Alliance (UPGA) with the Action Group, the Northern Elements Progressive Union (the main opposition party in the Northern Region), and the United Middle Belt Congress (a non-Muslim party strongly opposed to the NPC). In the UPGA coalition my father played a major role as deputy to the iconic Alhaji Aminu Kano, establishing what became a lifelong friendship with him.

As a child growing up under my father’s wings, I witnessed all these activities that he was involved in. I remember him on so many occasions meeting leading political figures like Aminu Kano, Ahmadu Bello, Michael Okpara, Nnamdi Azikiwe and many, many others. A lot of them came to our homes to meet with my father. Azikiwe was a frequent visitor. I remember much later listening to Azikiwe give a lecture to a large crowd of students and faculty at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka and hearing him mention my father’s name as one of his closest confidants who played a major role and contributed to the fight for independence. I was very touched by that and became prouder of my father.

Yes, my father’s politics was very progressive because he thought more about the future of his people and about how he could use his ideas to bring succor and peace to the people. In so doing, he became a giving person as he leveraged his position to lift up the conditions of others. This, no doubt informed my philanthropic orientation and disposition.

ATM: Apart from parental influence, what else from your childhood disposed you towards philanthropy?

DOA: I believe that apart from the influence of my parents in my philanthropic drive, I am disposed to doing the little that I do because of my belief that humanity and human existence must be preserved. Upon encountering the suffering and privation that have befallen the poor and less-privileged members of our society, especially in the rural area, it became clear to me that without private contribution to uplift the condition of these people, our society will decay and deteriorate to levels that will cause anarchy and general disintegration.

The fear of the scenario I just mentioned, and the dire consequences, and the compassion I feel for the needy, disposed me toward philanthropy.

On His Philanthropy

ATM: Your speech at the handover ceremony of Udeozo Primary School provided deep insights about the values driving your philanthropy. Do you see yourself as a crusader helping with the moral rearmament of society? Also, your philanthropy is currently focused on education at elementary school level, right? Could you tell us why you focus on education in general, and primary schools in particular?

DOA: I do not see myself as a crusader; rather I would prefer to be seen as purveyor of exemplary life, as someone who helps by providing essential tools (through quality education) that will help develop and re-orient the minds of our children. I believe very strongly that for any human to have high morals, the beginning of that person’s life is a critical point in time. The moral rearmament of our society must begin with our children. Give them good education that is grounded in the teaching of high discipline, the fear of God and great moral values, and you have built a great nation of morally upright men and women.

For this reason I have, for now, focused part of my philanthropy in education, especially in that of very young children. In setting up our Foundation, one of my major considerations was to entrench the Foundation in the redemption of the moral fiber of our society that has been gravely weakened, thus jeopardizing our basic our existence as humans. I believe that we can only fight this decay by investing in our children, because I still see our situation as not hopeless and completely lost, and that through the rebuilding of our children’s minds, we can fight these forces of retrogression.

I have written and spoken about the establishment of my philanthropic charity as being borne out of the belief and conviction that no form of human endeavor will thrive well without a properly secured liberty, happiness and equality that will create virtue and a sense of belonging in people, especially in our children during their formative years. You cannot expect a child with limited resources and impoverished education to live a progressive and normal adult life. Therefore, it is our collective responsibility as members of our society, to have moral disposition to public selfless interests.

ATM: You have completed three school projects so far, from available materials. These are Udeozo Memorial Primary School, Amudo, Agulu Community Primary School, Umuike, and Amaenyi Community Primary School Ayom na Okpalla. What informed the choice of these schools as the first tier of your school’s renovation project? What specific considerations in general inform your choice of beneficiaries – Is it the condition of the school infrastructure, or geographic dispersion?

Also, if you may, what other school projects are in the pipeline? What areas are targeted? At what stages of development are these upcoming projects?

DOA: I set up the Foundation to do various things and perform interventions in Education, Healthcare, Water, Environment, Child Welfare, Art and Culture, Religion and Moral Rearmament and in other areas where the need to provide lifesaving support and sustenance for the poor is most acute.

Yes, we have completed these three school projects. They are not renovation projects, though. They are three brand-new classroom block buildings purposively designed and built to the highest quality surpassing even most international standards.

We undertook a turnkey project for elementary schools in Awka; that is to design, build, equip and furnish them, also facilitate teachers’ training. Our plan is to build about 100 schools providing about 1000 classrooms, catering in total to over 50,000 pupils, mostly in Awka and surrounding localities. We have started and completed the three that you mentioned here which are strategically located in a spread-out pattern within various localities in Awka town.

We are now mapping out our next projects and putting into considerations demographics, needs and some balance issue to ensure that as many indigenes of the town as possible become beneficiaries of our charity.

ATM: Do you make the decision about beneficiaries all by yourself, or in consultation with anybody else? If the latter, which individuals or groups?

DOA: The initial decisions are made by me, and thereafter

consultations are made with the Trustees of our Foundation who contribute their individual and collective ideas and opinion. Through this interactive process we make the final decisions about the beneficiaries.

The members of our Board of Trustees are myself as the Chairman; my wife Hadiza and daughter Tochi, both lawyers, as member and Legal Adviser respectively. Others are Professor Ralph Oranu, Mr. Chris Obuekwe and Mr. Emeka Okoye. These men and women have been tremendously helpful and have provided visionary guidance that has ensured the success of the Foundation so far.

ATM: Do you make the decision about beneficiaries all by yourself, or in consultation with anybody else? If the latter, which individuals or groups?

DOA: The initial decisions are made by me, and thereafter consultations are made with the Trustees of our Foundation who contribute their individual and collective ideas and opinion. Through this interactive process we make the final decisions about the beneficiaries.

The members of our Board of Trustees are myself as the Chairman; my wife Hadiza and daughter Tochi, both lawyers, as member and Legal Adviser respectively. Others are Professor Ralph Oranu, Mr. Chris Obuekwe and Mr. Emeka Okoye. These men and women have been tremendously helpful and have provided visionary guidance that has ensured the success of the Foundation so far.

ATM: Who are the major partners to your Foundation?

DOA: We have no partners to our Foundation. All the projects we have done for several years have been from our private resources. This was intentional as we wanted to utilize our personal resources before asking for partnerships and external support. However, this position is changing as the realization of the enormity of the problems and the needs are rising above our private capacities. We are seeking out assistance for intangible help like training of teachers from overseas resource groups and medical assistance for hospitals in Awka and for some other Anambra State hospitals.

Presently, we are in advanced discussions with a major School System in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, to send us a corps of teachers, on a biannual basis, who will bring new ideas in teaching and introduce new curriculum that will broaden our children’s horizon in knowledge and expand their experiences, making them very competitive internationally. When this is implemented, an elementary school child from Ifite or Umuokpu village in Awka will be able to speak fluent French and Spanish as well as have skills in pure and applied IT sciences. I am very hopeful that the day is not too far to make this a reality.

ATM: Do you receive or seek any support from the government?

DOA: We have not sought nor received any support from government. Is it not this same government that has long left our children’s education, healthcare and lives in a state of total dilapidation?

ATM: Do you blame the government for the decay in educational infrastructure in Awka?

DOA: Is it not obvious that our governments from local and state to the federal tiers have long abdicated their responsibilities to our people? Of course, I blame them for not providing or sustaining the enabling environment that will make learning conducive and desirable. Have you seen these classrooms where our children study? They constitute eyesores and gross endangerment to human existence. Even animals should not be subjected to the debased environment under which these children study. I am therefore in a hurry to do my best to rescue these children from being subjected to study in classrooms unfit for the raising of pigs.

ATM: What are the specific details of the teacher training component of your schools project – who qualifies? what do they enroll for? how long is the teacher training programme? which are the training institutions? any beneficiaries yet?

DOA: The aim of training the teachers in our schools project is basically to develop their capacities and ensure progress and desired achievements of the children in the classroom. We are driven by the desire to change the face of education in Nigeria and we seek to train and empower teachers to be able to accelerate this process. The teachers are trained in improving communication and language of the child, effective teaching and classroom management and leadership in the 21st century school environment.

All primary school teachers are qualified for the training but the trainings are conducted in batches. The head teachers of the selected schools nominate teachers for every batch of the training. The teachers enroll to acquire new learning and teaching styles and skills in a responsive classroom environment. Each batch of training lasts for three days of intensive and rigorous work. They are also taught the integrated cross-curricular approach to teaching and learning.

We are deploying various training institutes in and outside of Nigeria to handle the various training programmes we have established.

At the moment, teachers of the three schools we have built have so far benefited from our training programme. Periodically, more teachers will undergo similar trainings.

ATM: You quoted Reinhold Niebuhr in your speech at Udeozo to the effect that “nothing that is worth doing can be achieved in a lifetime”. Do you not consider your philanthropic work so far to be substantive achievements?

DOA: To me, nothing in one’s life can ever be considered substantive enough. Achievements are measured according to one’s subjective views and considerations. I have never measured my achievements, as that should be left to others and ultimately in God’s hands.

I only derive my personal measurement when, in my private moments, I feel that I may have touched positively the heart and life of someone who does not even have a clue of who I am. That gives me immense satisfaction.

ATM: You are obviously still a young man, and your father did live to be 100. But have you started putting succession structures in place or even started to think about the leadership and strategic direction of the philanthropy after you retire?

DOA: Young man? Not that

young though. My father lived a very virile and purposeful life. Until he died at 100 years a few years ago, he was as fit as a fiddle. He rarely used a cane to walk, and his brain and memory remained razor-sharp. He was a repository of knowledge and history.

Philosophically, I do not have an inclination to think that it is in our places or authorities to build succession structures in terms of human structural elements through families or associates. In my opinion, those pre-planned ascendency imaginations do not flourish, and even when they do, they do not do well. Take a look around and see the big families from the Azikiwes, the Awolowos, the Akintolas, the Ojukwus, the Aminu Kanos, and tell me what have become of the succession structures they built for their children and families to inherit and sustain.

I will leave it to God to build and nurture the succession structure that will progress and direct the affairs of my philanthropy long after I am gone.

ATM: Any challenges currently faced by your philanthropy? Any anticipated?

DOA: Of course there are always challenges. We experience the paucity of funds to face the ambitions programmes that we have planned out. The needs of our people far outweigh our resources and this had been an ever-present challenge for us.

ATM: Do you think that Awka has other notable individuals who can take up philanthropic work at your level?

DOA: Yes I do. I know that our town Awka is blessed with an abundance of talented people in business, academia, politics, and public services. Many possess tremendous amount of goodwill and patriotic love for our town enough to solve most of our perennial problems through philanthropic work.

On Awka Development

ATM: What do you think about Awka today in terms of the spate and pattern of urban development?

DOA: I do not think of Awka as a town that has reached, let alone sustained, the level of development expected for a state capital. Nor do I think that it can attain that level of development in this century!

If one may venture to be blunt, the town is a glorified slum in terms of its infrastructural development. The hazardous plan of the town and the continuing degradation of its already “shanty” outlook, is truly disgraceful. Whenever I visit the once beautiful, clean and serene town and see the decay and chaos, I begin to long nostalgically for the old Awka before the rude invasion of these politicians with their vacuous talk, their blindness and lack of vision.

A drive through the Eke Market – a market whose construction my father, through community effort, superintended – will disappoint any discerning person. The market built in 1970 right after the devastation of the civil war has deteriorated beyond comprehension.

ATM: Awka town is currently embroiled in leadership acrimonies. How do you think this affects the development of the town?

DOA: I do not see any direct correlation between these leadership acrimonies and the development of Awka. We have had similar acrimonies in the past. In the period following the civil war when the “Ichie or no Ichie” issue was raging, my father presided over a divided Awka as chairman of the town union and was able to rebuild the market from the ruins of the war, build a brand-new modern Post office, construct a modern water works that supplied the whole of Awka with clean portable water, amongst other valuable projects.

The actors involved in these acrimonies, if they mean well for Awka, can continue with their political games and gimmicks and at the same time promote and execute projects that will serve Awka and its desperate poor and needy. In short, they can chew gum and walk at the same time.

ATM: Do you think that the Awka Development Union Nigeria (ADUN) should be spearheading the type of projects that your philanthropy takes on?

DOA: I do not think so, not just because of the known fact that they do not have the capacity but because they should focus on other intrinsic issues that may have serious consequences if not

properly addressed. Issues like intergovernmental relations on matters that affect Awka. The ADUN should be a strong lobby for the interests of Awka. They should ensure that Awka land, culture, dialect, traditions and ways of life are preserved, protected and vigorously defended both internally and externally.

I am equally worried about the activities of the ADUN in the Diaspora. I think, and I say it with a bit of trepidation, that these various groups operating from overseas, despite their good intentions, are misguided and do not understand the roles they should play in the affairs of Awka. These Diaspora groups have replicated the quarrels and disunity from Awka and perfected them with dexterity. From leadership tussles to impropriety issues, the Diaspora groups are in fragmented spin. How would one expect growth from a disunited group?

Apart from the imbroglios in which these Diaspora groups are mired, I suspect that their activities aimed at supporting infrastructural development in Awka lack vision or clarity. I had the good fortune of attending one of the annual Awka events held in Atlanta several years ago. The turnout was incredible and the social activities were colourful and very well planned and portrayed a fabulous festival evening for attendees. It was indeed a very beautiful and proud outing for our people.

However, on the day for the colloquium to discuss substantive issues, the topic and the discussants focused on the infrastructural support for Awka by the ADUN in Diaspora. I was disappointed with the deliberation because I had thought that we were missing the mark. When I was invited to speak, I advised that the focus of the Diaspora group should not be on infrastructural development for Awka, that instead it should be more on how to foster internal unity amongst the various groups and on how to internally establish institutions overseas that will teach our children growing up in America, Europe, Asia and in other places outside Awka, our way of life; our Igbo language, Awka dialect, our food, our culture – to impart on these children the pride of being from Awka.

I suggested that instead of buying transformers, scanning machines and other equipment that may not work in Awka because of certain incompatibilities, they should think of building centers in various cities where our mothers living in America will, on weekends engage our children and other interested people to learn the Awka way of life and Igbo culture in general.

Ten years or more after this beautiful event in Atlanta, these Diaspora groups are still fighting for leadership and planning on sending transformers that we do not need in Awka, as you can only transform power or electricity when you have it.

ATM: Has the town union leadership reached out to you regarding your projects?

DOA: No, they have not, and I do not care if they do or not, for these projects that we started over 20 years ago in Awka are not done for anyone to reach out to me.

A few individuals from Awka and outside Awka and even from elsewhere in the world have reached out to me to express joy and appreciation for what my Foundation is doing, encouraging me to do more.

ATM: Awka has been on what one may consider a 60-year transition from an acephalous republic to a monarchy, in the process suffering severe convulsions and setbacks. Do you think the transition to monarchy is wrongheaded, or is Awka moving in the right direction?

DOA: This is a very difficult question for me. I will attempt to answer it as tactically as I can due to the sensitivity of the issue in Awka today. Like I said in a portion of this interview, my father was a brave, upright and fearless man, and he meticulously taught me and imbibed those values in me. I will frankly speak my mind and what I consider in my humble opinion to be the truth.

The acephalous and, if you may, the republican nature of the Awka people from historical antecedents was instituted by our ancestors whom I consider to be very wise and great philosophers. The fact that they created a constitution that allotted “kingship” to the oldest was indigenous and a masterpiece in itself. There were no acrimonies as the oldest was always not in doubt and the position was never contested.

Until the importation of alien culture and tradition into Awka in this so-called chieftaincy nonsense, we lived in total peace, harmony and tranquility. Granted that cultures and traditions are dynamic elements of any people, the introduction and imposition of this anomaly into our culture has wrecked our town.

I do not believe that Awka should have a “king”. I have silently protested this anomaly for decades. My father stood on this same ground when he opposed it in the past. He, however, gave in to the pressure that every town is doing “this thing”, and that it was required for the modernization of our culture , that its acculturation or assimilation was necessary to survive and interact with government and other towns that have done “this thing”.

I took the “Awka Enwe Eze” (“Awka does not have a king”) mantra and its exaltation of the general will and buried it deep inside my psyche. I have made sure to stay away from the goodies and the animosities or acrimonies that have followed in the wake of the kingship issue which is strangulating the town. I was twice invited to be adorned with a chieftainship title but I declined.

Today, Awka has a monarch who has been on the throne for decades but I heard that his crown is under threat. Is this not comical? Our forefathers must be turning in their graves and wondering what has become of their children. We delude ourselves when we think that we can control the destinies of a people; that we own the moment and time. Philosophically, I know that time is infinitely here and will [continue its progress in perpetuity]. It is we as humans that [are transitory], that shall all die leaving time in its [majestic infinity]. We are wasting ourselves when we continue to desecrate the ways of our lives instead of making [productive] use of our time on earth.

ATM: Do you think that your stature in Awka, Nigeria and the world at large can be leveraged to resolve the current leadership disputes in Awka?

DOA: To be honest I do not consider myself to have much stature anywhere. I always see myself as an ordinary person. I may have been endowed with a fantastic pedigree, a great parentage, a solid education and a modest work success, but I was brought up not to see those attributes as a status or a symbol of success, but as a call to service.

When the war ended my father abandoned his thriving business and stayed back in Awka to support his people. His friends and contemporaries were in the Federal Government and they begged him to return to business, promising to give him huge contracts, but he declined and gave his entire life, blood, sweat and tears to the Awka people. My mother called him “Mr. Awka First”, as he spent over 18 hours every day working for Awka, leveraging every contact he had to rebuild Awka. His immediate family suffered for this, but he toiled and toiled for this town and for the welfare of its people.

I once asked my father if it bothered him that the Awka people did not care or recognize his sacrifices. He just smiled and told me that it did not matter, and that what matters is that God gave him an opportunity to serve HIM through the Awka people.

Like my father, I will serve Awka and its beautiful people and humanity with all my might until I take my last breath.

ATM: Would you ever consider following in your father’s footsteps to get involved in politics?

DOA: NO!

I have absolutely no interest in getting involved in politics in any shape or form. I feel sorry for our so-called politicians when I hear them refer to their profession as “politics”. I wonder if members of this class look around themselves to see the havoc their profession has wreaked in our country. There must be a very few exceptions, but most of our politicians are a disgrace to their profession, or vocation as I would have preferred them to call the trade that they ply.

When my father practiced politics, they were committed to the emancipation of the downtrodden. They used their positions to canvas for the liberation of our country from colonialism and thought more of the followers as human beings rather than tools who were used for votes and for the intimidation of opponents and people with different ideas and dispositions. They were accountable to the electorate, and the voters held them responsible for failing to deliver on their promises.

But today both the politicians and the electorate are irresponsible. They both think of what they can take out of the system and the State without caring what damage their actions do to the entire system. It is therefore difficult to see myself belonging to this group that calls itself politicians. Despite the fact that a few of them are still good people, the ratio of the good to the bad is so disproportionately low.

Until the entire system is awakened and overhauled to the reality that our political constituencies are theaters for making huge impact in the affairs of the generality of the people, I will keep a safe distance from politics and its chalice of polluting charms and smelly allures.